In sports and training there is a concept of “becoming an athlete before starting sports career”. We hear a lot about very successful prodigies who start to specialize in particular sport (or other activity) early on. But for professional athletes and definitely most of the people it is essential to develop strong base of general physical preparedness known as GPP.

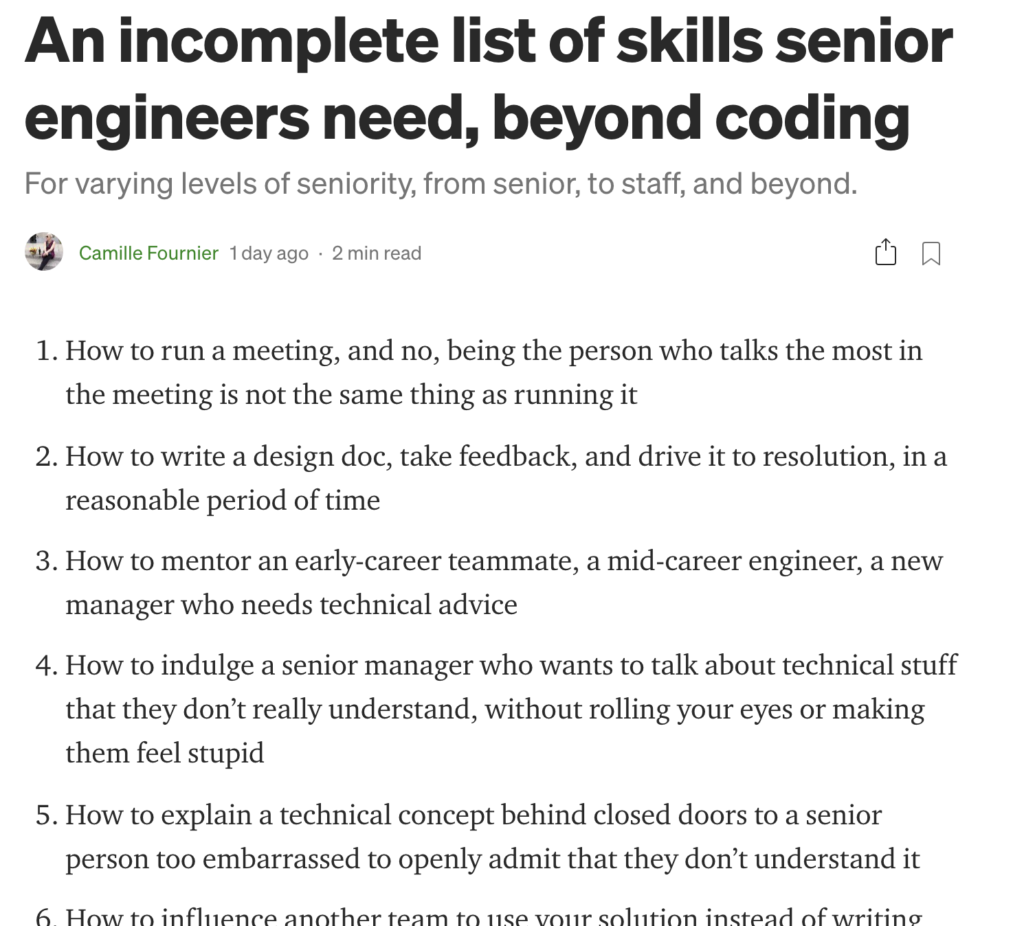

Today we’ve been reminded that similar General Professional Preparedness is important at work too:

This list is excellent, and applicable to wide range of professionals. For science undergrads, PhD students, and postdocs we can have extended list (on top of the linked above):

- Experimental design and agile troubleshooting

- Not-taking in meetings and running efficient lab notebook

- Collaboration on publications (especially as “last” author or the most interested party)

- Conflict resolution and negotiation skills

- Writing skills (including writing/publishing alone or just without PI)

- Mentoring skills (including sponsorship skills)

- Teaching (formal and informal, for all levels: senior colleagues and juniors mentees)

- Presenting skills (including job interviews)

- Searching for jobs (starting at undergrad level, e.g. writing CV, cover letter, reaching out to PhD advisers, finding the right fit)

- Searching for employees and interviewing candidates

- Asking for help, and efficiently seeking advice/support

- How to pitch (cover letters to editors, funders etc) and deal with rejections

- Basic employment skills

All these skills are “taught” during scientist’s career, but almost never formalized or emphasized by the supervisors. For example, writing is taught through editing and excessive use of red ink. Mentoring is almost never taught, and just passed along as bad (or good) habits from person to person. Learning how to search for a job is almost never part of the academic process as well. A lot of these skills, however, are discussed especially on Workplace StackExchange.

Academic groups, especially PIs, have no time and inclination for most of this work, and perhaps consider it to be extra-curricular activities. However, these skills are really the core of any professional performance. If PIs are not willing to invest personal time into teaching these skills, they should at least emphasize that these skills can’t be acquired without practice and focus, yet still essential.